The Great Unwashed

By Benjamin Feldman

Walk the moonscape of far East 38th Street today: the sidewalks are empty, devoid of life, though the streets hum and clog with traffic at rush hours as the entrances and exits to the Queens Midtown Tunnel spill forth. Those who emerge from the taxis and limos are well-scrubbed, their private baths drawn and terry robes donned. Toilettes in the neighborhood were not always this way. Where once, sidewalk games filled the air and factory whistles shrilled their shifts, not a trace remains of life as it was, circa 1900. Close your eyes and imagine the Gashouse District. It’s open to question if improvements have come.

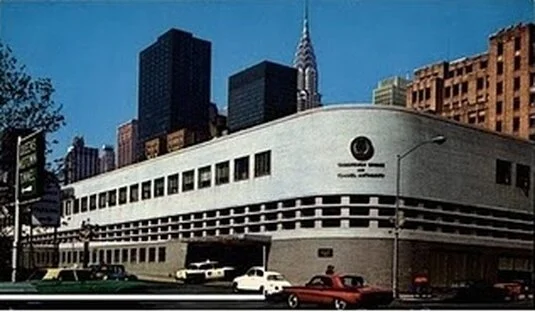

The ultra high-rise Corinthian apartment house and an unused, sterile First Avenue garden frontage dominate its 38th Street block. 50 years back, the pavement roared with smoke-spewing buses headed in and out of the old East Side Airlines Terminal, bound for Idlewild.

The express truck warehouse at the northwest corner of First Avenue was long ago converted to office uses, and at #325 a mauve-brick building houses the Philippine mission to the United Nations, its several street-side entrances hinting of a former use.

Few remnants exist in these northerly reaches of what was known for over a century as the Gashouse District. Con Ed’s Waterside generating station, torn down for Sheldon Solow’s latest and greatest development, stood among coal-gas storage tanks across the Avenue that decorated much of the East Side in the 20s and 30s, between the East River and First Avenue.

Tenements covered many of the small lots in the East 30s from 1890 onwards. Their residents found employment just yards from their vestibules: the Hupfels brewery and the Hoffman Cigar factory were two of the largest non-energy enterprises near #325. As late as 1899, many lots in the immediate vicinity either vacant or the site of ramshackle wooden structures devoted to low-skill industrial or agricultural uses. Abbatoirs and packing houses filled the streets just north of 42nd Street from the early 1850s until the United Nations was constructed in 1952. Take a sharp-pointed trowel and dig into the architraves over the identical doorways to #325. Your efforts would yield a clue of the building’s former importance to its neighbors. These separate men’s and women’s entrances meant sanitary facilities, back in the day. Turn of the century photos from the Byron Studio tell the tale.

1899 Map of the Area, courtesy of The New York Public Library.

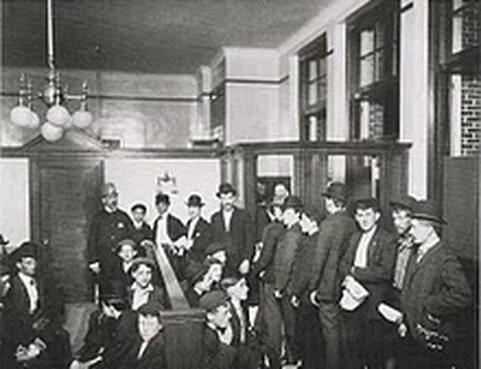

Photo courtesy of the Byron Collection – Museum of the City of New York

Barefoot and filthy, a bareheaded boy in ill-fitting, unbelted knickers stares at the camera, in the second shot, standing on the sidewalk in front of #325 on a late afternoon in 1904. His pals surround him, a lone, braided girl striding by. Perhaps they’re taunting him, the two youngsters in sailor frocks and nautical caps standing around him, somewhat better off. On the stoop of #325 a gaggle of boys roosts, sporting skimmers, pushing at the western entrance door to the building, their school day at nearby P.S. 49 finally over. In the distance, the iron superstructure of the 2nd Avenue elevated train, appears (demolished in 1942), along with a gas-lit street-lamp. All we see in the photo is long gone excepting #325, its history and origins obscured by the years, a rare remnant amongst today’s icy glitter.

Although the city government began assuming responsibility for the construction of desperately needed public bathhouses in poor neighborhoods at the turn of the 20th century, private philanthropy did not abandon the public bath movement.

Water closets in hallways and simple taps in the kitchens were the most that could be expected in many late 19th century tenements in New York. Bathing was only possible by filling tin bathtubs from the kitchen tap, a cumbersome procedure in crowded and busy flats. A once a week full body was custom and practice, and many went without for longer periods of time.

Photo courtesy of the New York City Housing Authority archives at LaGuardia Community College

Hollow-eyed faces and clothes hanging off gaunt frames cover the photo of the interior of the men’s waiting room at the Milbank Baths, also taken by the Byron Studio in 1904. At the right, men wait in line, bowlers askew and towels in hand, while to their left, younger men cover the benches waiting their turn. A NYPD cop in a “bobby” hat stands guard in the back of the room, his stern visage insuring order among the handle-bar mustachioed fellows in the hall, 30 years of age and under for the most part.

In June 1902, Elizabeth Milbank Anderson announced that she would donate a public bath, to be built on a 50 by 98-foot lot on East 38th Street (#325) on behalf of the Association for Improving the Condition of the Poor (the “AICP”). Anderson was heiress to one of the founders of the Borden Condensed Milk Company and was a leading New York philanthropist. During her lifetime she donated approximately $5 million to various institutions, with Barnard College as the chief beneficiary. The bathhouse which she donated, known as the Milbank Memorial Bath, opened in January 1904. A large and imposing facility, it cost $140,000 to build and could accommodate 3,000 bathers daily. The AICP also built The People’s Baths at 9 Centre Market Place, across the street from the new castle-like headquarters of the New York Police Department. In 1914, after a canvass of the neighborhood, the AICP established a wet-wash laundry at the Milbank bath.

Mrs. Anderson (1850-1921) and her brother, Joseph Anderson, inherited an eight figure fortune, rumored to be as much as $32,000,000, in equal shares from their father. Jeremiah Milbank, whose success in his Front Street Grocery burgeoned into a fortune based on milk distribution and banking. Married at age 37 to artist A.A. Anderson (whose studio was located in the roccoco Bryant Park Studio building that still stands on the south side of Bryant Park on the 6th Avenue corner), Mrs. Anderson donated a large share of her inheritance to charity. She and her husband lived on East 38th Street also, but at the fashionable 5th Avenue end. Their residence at 6 East 38th Street undoubtedly included more than enough plumbing to avoid even the servants needing to use their mistress’ charity facility near the East River docks. Her largesse also included deeding three and one-half acres of prime Morningside Heights land between Claremont Avenue and Broadway from 116th to 119th Streets to Barnard College for construction of the Milbank Quadrangle at the northern end of the campus as well as Milbank Hall thereon, in memory of her mother Elizabeth Lake Milbank. Millions more were given to Barnard and to Teachers College of Columbia University to fund science instruction for women and other academic purposes.

Photo courtesy of the Byron Collection – The Museum of the City of New York

Money could not buy everything, though: In 1892, Elizabeth tried to impose her friend Dr. Francis Kinnicutt (Secretary of the Children’s Aid Society) as the director of a new medical pavilion at The Roosevelt Hospital, with his successor to be chosen by the “medical staff” of Columbia University, Roosevelt demurred, and the donation was aborted. The Milbank name is ensconced in the annals of New York philanthropy, physical reminders ever present in Morningside Heights and elsewhere in the metropolitan region. 105 years after its founding, funds originally provided by Elizabeth Milbank Anderson continue to support the operations of the Milbank Memorial Fund, which, according to its website “is an endowed operating foundation that works to improve health by helping decision makers in the public and private sectors acquire and use the best available evidence to inform policy for health care and population health. What we take for granted today in New York for all but our poorest and usually homeless residents was once neither easy nor commonplace. The very basis of public health, a daily bath, and clean laundry facilities were made available to legions of Gashouse District residents by the Milbank largesse. It’s hard to believe when one stands on the sidewalk. #325′s stoops once teemed with needy visitors. Today they’re all but silent. Imagine those days.

Benjamin Feldman is the author of Butchery on Bond Street: Sexual Politics and The Burdell-Cunningham Case in Antebellum New York and Call Me Daddy: Babes and Bathos in Edward West Browning’s Jazz Age New York. His essays have appeared in The New Partisan Review, Ducts literary magazine, and on his website, The New York Wanderer.